Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Twin Sisters

Lara Taubman

Typically a critic of painting and sculpture, I find the intractability of ceramics exceptional. In a time where it is central to contemporary art that any and all mediums are acceptable, I am interested to see how ceramic sculpture manipulates and flirts with issues of form and surface.

In ceramics, ideas are eternally wedded to the ancient vessel; at some level, the process of any ceramic piece begins and ends on this note. The history of contemporary ceramics possesses countless riffs on the way a surface can appear from hyper-realistic, exact replicas of actual objects to enhanced natural surfaces of earthen glazes. Indeed, the surface invention is limited only to the imagination, skill, and experience of the artist, manipulating attributes of the clay vessel form that has been a steadfast tradition for thousands of years.

Between Clouds of Memory, a mid-career survey of ceramics by Akio Takamori (Arizona State University Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona) proves him to be a master of the clay vessel, but, more importantly, an artist absorbed in his personal musings between the ceramic form and its surface. Twenty-five years of work produces this small but densely packed exhibit of ceramic vessels, sculptures, drawings and prints.

The drawings and prints directly inform Takamori's ceramics works, working out his narratives and ideas two dimensionally; it is the space where the issue of the vessel is a less direct conceptual concern for him. The draftsmanship is more relaxed and liberal. The loosely drawn narrative lines and shapes re-appear on the vessels but they arrive on the surfaces looking as if they had been made in another place.

Takamori always tells two stories at once, one on the surface and one in the form. Like a car that has two engines that move at varying speeds, one of these narratives is woven tightly to the form and another exists in a realm of Takamori's mind where the viewer goes uninvited. This tension is at times uncomfortable, even pretentious or coy, because he does not divulge his secret stories evident in the descriptive surfaces. The lines speak but not of the vessel upon which they have been applied. They are suspended in space and time without a clear resolve that goes hand in hand with a completed statement.

In his more recent sculptures, descriptive lines float atop the vessel's surface like oil on water leaving rhythmic gaps of silence. Each of his poignant lines speaks a chapter, the vessel itself becoming the story. In earlier works, the two narratives characteristic of Takamori are still in play but the discrepancy is not as harsh. In either case, the work is beautiful and clearly that constant scrutiny of his mediums are the rigor that sustain the seriousness of these vessels.

The back and forth journey between form and narrative for Takamori is the flow, both conceptual and physical, that drives these works, and throughout his career. His work is so idea driven that it does not look similar between series but it does maintain a bond of intent. Sacrificing visual certainty, he jettisons back and forth for lower contrast areas gray: large to small, dark to light, close up to far away. His ideas expand and contract as through a telescope. For instance, his earlier works are actual places depicted and viewed from a distance blurring details into generalities. The recent statues of people are, by contrast, extreme close-ups.

The minutiae of Takamori's early work, "Village," a diorama of a Japanese village, fall in and out of focused recognition much in the same way that memories become concentrations of only important details. One may recall an idyllic childhood setting, the bark of a tree, or an arguement with a friend from many years before. A memory may be as sharply focused as the actual ocurrence may be blurred.

The "Village" realizes Takamori's memories, not the events as concrete and hyper-real. The visual impact is of a whole greater than the sum of its parts - these being the individual narratives that certainly are the foundation of his village. There he finds the safe haven, an identity in memory, of home; this is a place that reassurancedly reflects that he exists.

Takamori is perhaps best known for his passionate vessels of the nineteen-eighties that are well represented in this show. Eternal topics of love and daily life are interpreted through equally intelligent and romantic vessels. Tumultuous episodes of lovemaking are of Shakespearean proportion in their metaphorical and dramatic portrayal.

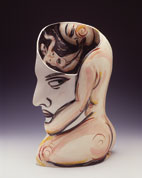

In "Spring" (1988) , two black and white lovers dance around the form, their ecstatic lovemaking locking the form together in tension. "Her Love" describes a hierarchy of love between woman and man. Literally gazing into the man's mind, the woman embraces him with the nurture given to a child, a father and a lover.

This series is a joyous, harmonious, engagement between form and function, flirtatious and playful. The vessels undulate playfully between serious aesthetic issues and "how would the vessel look with flowers in it?" These works combine rhythm, color and form both in the generously glazed surfaces and the complex and delicate porcelain.

Work of a high tenor can only exist for a period before it becomes trite and Takamori moved on before being caught in this trap. His eventual departure for the equally playful, but more austere, human sculptures is a logical transition for one whose seriousness seems to be the final word during his creative process.

Masterworks such as "Empress" and "Queen" reference history and art history while making a powerful use of sculpture and drawing. In "Empress," the Japanese royal subject stands thigh high to the viewer, but, like all the statues, commands a disarmingly human presence. Decorated partly like a large Japanese vase, the descriptive, black lines of the Empress's robe, hair and feet float off the surface creating a presence of austerity directing the viewer to look at this woman from within.

"Queen" presents a juxtaposition of royalty between the East and West. Referencing the little princess of the Velazquez painting "Las Meninas," she has grown up to be an unremitting, lofty queen. The detailed and complicated accoutrement of her dress bleeds with Takamori's intentional dripping marks that signify decadent Western riches.

These sculptures do not pretend to look human; they are cursory in their presumptions, infering the human form. Takamori has imbued these works with traces of human anima. With a semblance of self-reflection, they regard themselves more real than real, and more serious, than any life-like sculpture. They come across as self-absorbed or aloof but in either case, the viewer senses scrutiny glaring back at him from these clay vessels. Their presence is other worldly, sometimes uncanny and terrifying.

As these ladies (and their neighbors) verge successfully between fully human and not human, they are torn also between being vessel or sculpture. After spending time with the works, one sees that Takamori holds form in one hand and function separately in the other. He brings them together as a deliberate contradiction or collaboration, an act of which he is in total control.

The nuances of paradox are Takamori's final goal. He seeks a way to engage the clay, the idea and a devoted creative process. In moments he is successful, no quality out of balance or absent from the work. It emerges together as a unified visual dialogue. He has moments where the work stops being about medium or an attempt to convey an idea, looking as if it has existed for time immemorial. In a piece like "Sphinx," (2002) he generates disparate topics of the mythical past with his own personal present. His head sits upon the sphinx body as though upon history, a victim of his own self-imposed strangeness on this mythical animal of riddles and power.

The weirder he allows his ideas to be, and the more he lets them play out, the more successful the work. It is then that Takamori's strict dedication to art making, ceramics in particular, becomes less self-conscious. In these moments only beholden to his imagination, his own language, the full impact of his work is felt. Perhaps attaining a mastery of art is not the only challenge for Akio Takamori but owning his mastery when attained.

Links

Arizona State University Art Museum

Tenth Street and Mill Avenue

Tempe AZ 85287-2911

480-965-2787

asuartmuseum@asu.edu

asuartmuseum.asu.edu

Dance

Karako

Queen